Our contributor, Summer Stone of Cake Paper Party, is back today with a new baking science experiment….

Baking a truly exceptional cake is an art, but beneath every perfect crumb lies a fascinating layer of science. For home bakers and seasoned pastry chefs alike, understanding how ingredients interact during the mixing process is crucial for achieving desired textures and flavors. When it comes to butter cakes, two primary mixing methods dominate the culinary landscape: the classic creaming method and the increasingly popular reverse-creaming method. While both aim to produce delicious results, their distinct approaches yield subtle yet significant differences in the final cake structure, crumb, and overall eating experience.

Most traditional butter cake recipes employ the creaming method, a time-honored technique where butter and sugar are first beaten together to incorporate air, followed by the gradual addition of eggs, and then alternating dry and liquid ingredients. This method is celebrated for creating light and airy cakes with a tender crumb. In contrast, the reverse-creaming method, sometimes called the “paste method,” starts by combining all the dry ingredients, including sugar, before incorporating the fats and a portion of the liquids, with the remaining liquids added last. This unique sequence fundamentally alters how gluten develops and how air is incorporated, often resulting in a cake with a finer, more velvety texture.

To truly appreciate the nuances of these techniques, our contributor, Summer Stone from Cake Paper Party, embarked on a fascinating baking science experiment. Her goal was to dissect the impact of each mixing method on a basic butter cake recipe. By meticulously preparing three identical cake batters—one using the creaming method, one with the reverse-creaming method, and a control cake where all ingredients were mixed simultaneously—she aimed to provide a clear, comparative analysis of the final outcomes. This hands-on approach offers invaluable insights into how these mixing strategies directly influence cake characteristics, empowering you to choose the best method for your baking endeavors.

The Science Behind the Mix: Understanding Each Method

Before diving into the delicious results of our experiment, let’s explore the scientific principles underpinning each mixing method. Grasping these fundamentals will help you understand why each technique produces its distinctive cake qualities.

The Classic Creaming Method: Achieving Lightness and Air

The creaming method, also known as the conventional method, is the most widely adopted technique for butter cakes and often the first one bakers learn. Its popularity stems from its reliable ability to create cakes with a wonderfully light, open crumb and a tender texture. The key steps are meticulously designed to maximize air incorporation and control gluten development:

- **Aeration through Butter and Sugar:** The initial step of vigorously beating softened butter with granulated sugar is perhaps the most critical for leavening. As the jagged edges of sugar crystals cut into the butter, they create tiny air pockets. These trapped air bubbles are crucial for the cake’s rise during baking, expanding from the heat and contributing to a light and airy structure. Proper creaming ensures significant volume increase and a pale, fluffy mixture.

- **Emulsification with Eggs:** Eggs are added one at a time to the creamed butter and sugar mixture. This gradual addition allows the eggs’ emulsifiers (lecithin in the yolk) to create a stable emulsion with the fats, preventing the batter from curdling. Thorough emulsification ensures a smooth, homogeneous batter, which translates to a consistent and even texture in the finished cake.

- **Controlling Gluten with Alternating Additions:** After the eggs are incorporated, dry ingredients (flour, leaveners) and liquids (milk, buttermilk, etc.) are added alternately in several stages, usually starting and ending with dry ingredients. This sequence is strategic. Adding dry ingredients first helps to absorb moisture and prevents the batter from becoming too wet, which could lead to excessive gluten development. Alternating with liquids allows for better hydration of the flour without overworking the gluten, ensuring a tender crumb rather than a tough one. This method also minimizes the risk of over-mixing.

The creaming method is ideal for cakes where a delicate, open texture and a pronounced lift are desired, such as classic vanilla, chocolate, or lemon butter cakes. The air pockets created in the initial stage are the primary source of leavening, contributing to the characteristic fluffiness.

The Reverse Creaming Method: For a Fine and Velvety Crumb

The reverse-creaming method offers an alternative path to cake perfection, particularly favored when a dense, velvety, and exceptionally fine crumb is the goal. This technique fundamentally changes the order of operations, influencing ingredient interaction differently than the classic creaming method:

- **Fat-Coated Flour for Gluten Inhibition:** In this method, all the dry ingredients, including flour, sugar, and leaveners, are combined first. Then, softened butter (or other fats) is gradually added and mixed into the dry ingredients. This crucial step coats the flour particles with fat before any liquid is introduced. By encasing the flour proteins in fat, gluten formation is significantly minimized. Less gluten development results in a more tender and softer cake, preventing toughness and dryness often associated with overmixing.

- **Controlled Hydration and Structure:** After the fat is thoroughly mixed into the dry ingredients, forming a sandy or coarse crumb mixture, a portion of the liquid ingredients (often milk or buttermilk) is added. This initial small amount of liquid helps to hydrate the flour gently and begin to develop some structure in the batter without activating too much gluten. It allows for a smooth blending of the fat-coated dry ingredients, creating a more uniform base.

- **Minimal Air Incorporation for a Fine Crumb:** Unlike the creaming method that actively incorporates air, the reverse-creaming method focuses on minimizing air pockets. The fat/flour mixing process ensures that any incorporated air particles are tiny and evenly dispersed. This leads to a very fine, tight crumb structure that feels dense yet moist and melts in your mouth. This characteristic makes reverse-creamed cakes particularly suitable for carving or stacking, as they are less fragile.

The reverse-creaming method excels in producing cakes with a luxurious, velvety texture and a tightly structured crumb. It’s often preferred for specialty cakes, such as those used for elaborate decorations, or when a rich, moist, and slightly denser cake is desired, capable of holding up to fillings and frostings. Its inherent resistance to overmixing due to the fat-coated flour is another significant advantage for busy bakers.

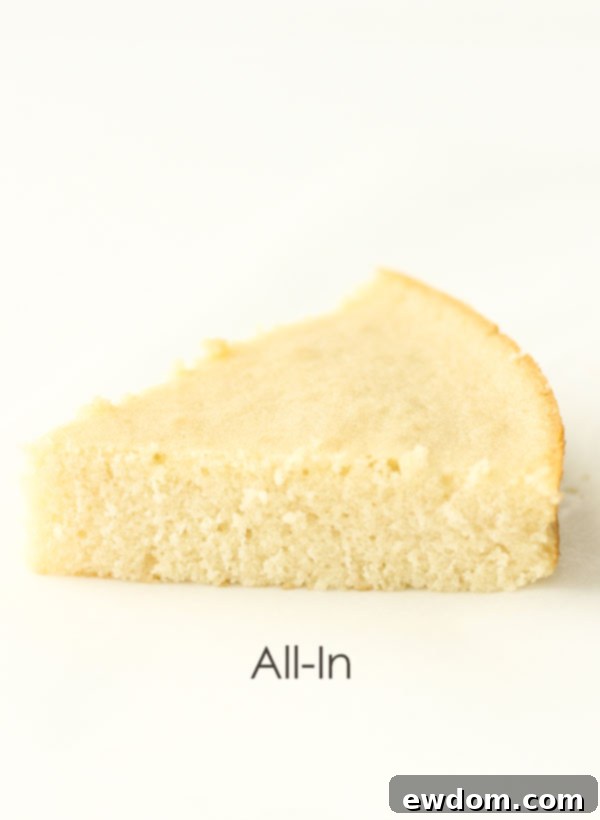

The All-In Method: Simplicity with Compromises

For comparative purposes, Summer also included a control cake prepared using what she termed the “all-in” method. This technique involves combining all ingredients—butter, sugar, eggs, flour, and liquids—into the mixer at once and mixing until just combined. While undeniably the easiest and quickest approach, it comes with significant trade-offs:

- **Eased Mixing, Difficult Emulsification:** The primary benefit of the all-in method is its simplicity; it eliminates multiple mixing steps. However, without the sequential addition of ingredients, achieving a proper emulsion of fats and liquids becomes challenging. The high volume of liquid present from the start makes it difficult for fats to blend adequately and uniformly throughout the batter.

- **Poor Air Incorporation and Leavening:** Crucially, the all-in method incorporates very little air. The absence of the creaming step means no significant air pockets are intentionally introduced into the butter and sugar. The abundance of liquid also hinders the mechanical incorporation of air. This lack of initial leavening, combined with potentially less efficient chemical leavening due to poor mixing, typically results in a cake with significantly less rise and a denser, tighter structure.

- **Denser Crumb and Potentially Uneven Texture:** Consequently, cakes made with the all-in method generally have a much denser, tighter crumb and can sometimes exhibit an uneven texture. While still producing an edible cake, it often lacks the desirable lightness and tenderness associated with cakes made using more structured methods. This method might be considered a last resort for very specific dense cake types or when time is extremely limited and texture is not a primary concern.

Experimental Setup and Surprising Results

To provide a clear, apples-to-apples comparison, Summer’s experiment utilized a carefully chosen, basic vanilla butter cake recipe. This foundational recipe, with its balanced ratios of fat, sugar, flour, and liquid, served as an excellent baseline to observe the pure effects of each mixing method without confounding variables from complex flavors or unusual ingredients. Each cake was prepared with identical ingredient quantities, baked in the same oven at the same temperature, ensuring that any differences in the final product could be attributed solely to the mixing technique.

Having previously baked countless cakes using both the creaming and reverse-creaming methods, Summer anticipated distinct textural differences. In her experience, certain cake formulations tend to perform better with one method over the other, depending on the desired outcome. For instance, high-ratio cakes with a higher sugar-to-flour ratio often benefit from the reverse-creaming method for better moisture retention and stability.

However, the results of this particular trial with the basic vanilla butter cake offered an intriguing surprise. Summer observed that the cakes prepared using the classic creaming method and the reverse-creaming method were remarkably similar. Both exhibited a delightfully light texture and a moderately fine crumb—a testament to the robustness of a well-formulated basic recipe. This suggests that for simpler, straightforward butter cakes, both structured mixing methods are highly effective at producing an appealing result. The subtle differences that might emerge with more complex recipes or variations in ingredient ratios were less apparent in this foundational test.

As expected, the all-in cake, despite its ease, produced a noticeably different texture. It was discernibly denser with a tighter crumb compared to its counterparts. However, even this less sophisticated mixing approach yielded a perfectly acceptable cake, demonstrating the forgiving nature of some basic recipes. While it lacked the refined qualities of the other two, it was far from a failure, proving that sometimes, even a quick mix can deliver a satisfactory treat.

The Takeaway: Choosing Your Mixing Method Wisely

So, what can we glean from this insightful baking experiment? The most significant take-home message is one of informed choice and adaptability. For a very basic cake recipe, both the traditional creaming method and the reverse-creaming method are highly effective in producing a delicious and appealing cake. Your selection, therefore, can often come down to personal preference, the specific characteristics you’re aiming for, or the demands of your recipe.

- **For Lightness and Fluffiness:** If your goal is a cake with maximum lift, a tender, open crumb, and a light, airy texture, the **creaming method** is your go-to technique. It’s excellent for classic birthday cakes, cupcakes, and any situation where a delicate, melt-in-your-mouth feel is paramount.

- **For a Fine, Velvety, and Moist Crumb:** If you’re seeking a cake with a dense, velvety texture, a super-fine crumb, and enhanced moisture retention, the **reverse-creaming method** is an exceptional choice. This method is particularly advantageous when developing recipes that need to be sturdy enough for carving, stacking, or intricate decorating. It’s also fantastic for richer, more robust flavored cakes where a tight crumb complements the intensity.

- **For Speed or Specific Density:** While not producing the most refined texture, the **all-in method** can be a practical option if you’re in a hurry or if the recipe specifically calls for a denser cake, perhaps for a firm base in a dessert or a sturdy fruit cake. It sacrifices some finesse for pure convenience.

Ultimately, the beauty of baking science lies in the flexibility it offers. By understanding how each method influences your ingredients and the final product, you empower yourself to make deliberate choices based on the situation, the specific recipe’s needs, and your desired outcome. Experimentation is key to discovering which method resonates best with your baking style and achieves the perfect cake every time.

Happy baking!

Now read my article, Mixing Up The Perfect Cake.

See exactly how long to mix butter and sugar together!

Next see If Sifting Makes a Better Cake.

I think you’ll be surprised by my results!

And don’t miss my article, The Meringue Buttercream Myth!

It’s a unique new way to make Swiss Meringue Buttercream.